欢迎来到相识电子书!

标签:饮食

-

开麦拉美味幻想曲

《芭比的盛宴》的开胃酒Amontillado、海龟汤、佩里戈尔调味酱佐鹌鹑千层酥盒、Demidof风鱼子酱配苏俄薄煎饼、糖腌水果佐萨瓦兰蛋糕等美酒佳肴…… 在挑逗最原始的口腹之欲,或者,你刚看完《007系列》,念念不忘詹姆斯・邦德的豪华的东方快车上,到底是用哪一种香槟掠获了美女的心? 这部融合“第七艺术”电影及“第八艺术”美食的超级感官之书,将揭晓一切有关世纪“美味世影”里隐藏的美食秘密,邀请你一起身历其境。 -

中国古代饮食文化

《中国古代饮食文化》的前身有110个专题,涉及历史文化的各个方面,由商务印书馆、中共中央党校出版社、天津教育出版社、山东教育出版社联合出版。现由编委会对类目重新加以调整,确定了考古、史地、思想、文化、教育、科技、军事、经济、文艺、体育十个门类、共100个专题,由商务印书馆独家出版。每个专题也由原先的五万多字护大为八万字左右,内容更为丰富,叙述较前详备。希望这套丛书能多角度、多层次地反映中国文化的主流与特点,读者能够从中认识中国文化的基本面貌、了解中华民族的精神所系,这就是编者的最大愿望。 -

让我们害怕的食物

1.食品安全一直是社会热点,我们主要关心两点:食品安全吗?食物吃进去有益健康么? 2.这是一本篇幅适中、附有插图的社会史著作,处理的主要是现代美国人对食品安全、食物是否有益健康感到忧心的历史。 3.农药、添加剂、经过加工的食品会要人命吗?鸡蛋是否是“胆固醇炸弹”?红酒是否对心脏好却对肝脏不好?作者历史地看待了美国人对这一系列问题的看法。 4.作者的主要观点是,食品恐慌在很大程度上不见得是理性的,因受专家意见影响、受食品生产厂家鼓动而对食物产生偏见的情况屡见不鲜。诺贝尔生理学及医学奖获得者梅奇尼科夫宣称喝酸奶能让人活到140岁,因为它们能杀死肠道内的致命病菌。维生素的“发现者”Elmer McCollum剪裁自己在维生素缺乏症方面的理论,以迎合资助他的食品生产厂家的需要。作者也记述了大食品厂利用人们的恐慌心理,推销产品。比如所谓“天然食品”运动,认为喜马拉雅深山中的居民更健康长寿,因为他们的食物是纯天然的,未经处理。再如美国的营养学家、“地中海减肥法”的推动者Ancel Keys整合学者、医生、厂家等各方意见,提出高脂肪的食物是致命的。 5.作者对食物、食品安全持一种乐观态度,会给陷入食品安全恐慌中的中国人带来一种新的观察角度。 媒体推荐 引人入胜,发人深省。——《波士顿环球报》 如果说吃什么补什么的话,那么我们害怕自己前一天兴冲冲吃下去的食物又意味着什么呢?哈维·列文斯坦以坦率的叙述笔法记录了从19世纪90年代以来直到今天,曾席卷过美国的一波又一波对食物的忧虑,从新鲜蔬果带来的威胁(因为在露天市场里,苍蝇落在上面)到脂肪恐惧症(享用任何一种形式的高脂肪食物都被视为自杀行为)。这是一本深入探究食物恐慌史同时又非常有趣的书,一大批公众利益的捍卫者和营私舞弊的操作者在其中先后登场。 ——《泰晤士高等教育增刊》(Times Higher Education Supplement) 哈维·列文斯坦开出的药方是怀疑和独立思考。他在各种“责怪食物”运动的中心发现了道德主义的身影,他告诫我们,对其要有所提防,并提出吃绝大多数食物都应该适度,这才是保持健康的正道。 ——《华盛顿邮报》(Washington Post) 列文斯坦先生对美国人在食物上的恐惧和信仰的历史做了栩栩如生的描绘,且多有出彩之处,所有读者都能从中获益良多,今天的决策者、监管者、政治家、新闻记者和企业高管也同样受益。 ——《金融邮报》(Financial Post) 哈维·列文斯坦说,美国是一个陷入味觉偏执的国家。运用这种言简意赅而又风趣的叙述风格,他揭示了美国消费者是如何遭受长达数十年的焦虑之苦,只是为了一块猪肉或是鲜奶酪中的脂肪。他说,一大批科学家掀起了各种各样的恐惧浪潮,从细菌、维生素缺乏到添加剂到工业化加工,无意中培养出困扰了整个现代美国社会的进食障碍。列文斯坦呼吁对待所有的食物都要适度——当然也包括适度自身——这样才能重获美食的乐趣。 ——《自然》(Nature) 《让我们害怕的食物》是一本美味佳作。 ——《书籍与文化》(Books and Culture) -

今天也要好好吃饭

好的人生,从好好吃饭开始,好好吃饭,就是好好爱自己。人生的意义就是吃吃喝喝,就这么简单和基本。 好好吃饭是头等大事,每顿饭都会影响到日后的自己和生活的全部。要尽量地学习,尽量地经历,尽量地吃好东西,人生就比较美好一些。 《今天也要好好吃饭》是蔡澜对各地美食及与日常生活息息相关的食材的记录。看看每道菜的口味、形式和烹饪手法,还有字里行间透出的风土人情、世相人心和人生体味。让人不禁感慨,一辈子不长,要吃好,喝好,日子过好。 愿你也能每天都要好好吃饭,懂生活,爱生活,过好每一天。 -

皇家饮食调养指南

该书是一部古代营养学专著,全书共三卷。卷一讲的是诸般禁忌,聚珍品撰。卷二讲的是诸般汤煎,食疗诸病及食物相反中毒等。卷三讲的是米谷品,兽品、禽品、鱼品、果菜品和料物等。 该书记载药膳和食疗方非常丰富,特别注重阐述各种饮撰的性味与滋补作用,并有妊娠食忌、乳母食忌、饮酒避忌等内容。它从健康人的实际饮食需要出发,以正常人膳食标准立论,制定了一套饮食卫生法则。书中还具体阐述了饮食卫生,营养疗法,乃至食物中毒的防治等,为我国现存第一部完整的饮食卫生和食疗专书,也是一部颇有价值的古代食谱。 内容包括了医疗卫生,以及历代名医的验方、秘方和具有蒙古族饮食特点的各种肉、乳食品,甚至明代名医李时珍所著《本草纲目》也引用了该书的有关内容。 -

我爱咖啡

《我爱咖啡!》内容简介:献给所有热爱咖啡的人——无论是热爱咖啡的普通人还是专业的咖啡师——只要按照这《我爱咖啡!》中所介绍的简单配方操作,都可以调制出味美的热咖啡和冰咖啡饮品。在《我爱咖啡!》中,咖啡专家苏珊•吉玛和我们分享了专业的咖啡调制技巧和方法,包括如何调制完美的咖啡,如何在没有咖啡机的情况下制作味道很美的卡布基诺,以及加拿大咖啡师大赛冠军是如何创作出大师级的拿铁拉花的。《我爱咖啡!》囊括了全球的咖啡品种和独特的咖啡调制技巧,所有与咖啡相关的知识一应俱全——从咖啡豆到咖啡杯。《我爱咖啡!》介绍了100多种易于操作的咖啡配方,适用于所有场合,包括制作热卡布奇诺、冰咖啡、饭后咖啡甜点和经典的咖啡马提尼。《我爱咖啡!》所有配方均配有精美的图片,是一本调制所有咖啡饮品的终极教科书。 -

Fast Food Nation

CHEYENNE MOUNTAIN SITS on the eastern slope of Colorado’s Front Range, rising steeply from the prairie and overlooking the city of Colorado Springs. From a distance, the mountain appears beautiful and serene, dotted with rocky outcroppings, scrub oak, and ponderosa pine. It looks like the backdrop of an old Hollywood western, just another gorgeous Rocky Mountain vista. And yet Cheyenne Mountain is hardly pristine. One of the nation’s most important military installations lies deep within it, housing units of the North American Aerospace Command, the Air Force Space Command, and the United States Space Command. During the mid-1950s, high-level officials at the Pentagon worried that America’s air defenses had become vulnerable to sabotage and attack. Cheyenne Mountain was chosen as the site for a top-secret, underground combat operations center. The mountain was hollowed out, and fifteen buildings, most of them three stories high, were erected amid a maze of tunnels and passageways extending for miles. The four-and-a-half-acre underground complex was designed to survive a direct hit by an atomic bomb. Now officially called the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station, the facility is entered through steel blast doors that are three feet thick and weigh twenty-five tons each; they automatically swing shut in less than twenty seconds. The base is closed to the public, and a heavily armed quick response team guards against intruders. Pressurized air within the complex prevents contamination by radioactive fallout and biological weapons. The buildings are mounted on gigantic steel springs to ride out an earthquake or the blast wave of a thermonuclear strike. The hallways and staircases are painted slate gray, the ceilings are low, and there are combination locks on many of the doors. A narrow escape tunnel, entered through a metal hatch, twists and turns its way out of the mountain through solid rock. The place feels like the set of an early James Bond movie, with men in jumpsuits driving little electric vans from one brightly lit cavern to another. Fifteen hundred people work inside the mountain, maintaining the facility and collecting information from a worldwide network of radars, spy satellites, ground-based sensors, airplanes, and blimps. The Cheyenne Mountain Operations Center tracks every manmade object that enters North American airspace or that orbits the earth. It is the heart of the nation’s early warning system. It can detect the firing of a long-range missile, anywhere in the world, before that missile has left the launch pad. This futuristic military base inside a mountain has the capability to be self-sustaining for at least one month. Its generators can produce enough electricity to power a city the size of Tampa, Florida. Its underground reservoirs hold millions of gallons of water; workers sometimes traverse them in rowboats. The complex has its own underground fitness center, a medical clinic, a dentist’s office, a barbershop, a chapel, and a cafeteria. When the men and women stationed at Cheyenne Mountain get tired of the food in the cafeteria, they often send somebody over to the Burger King at Fort Carson, a nearby army base. Or they call Domino’s. Almost every night, a Domino’s deliveryman winds his way up the lonely Cheyenne Mountain Road, past the ominous DEADLY FORCE AUTHORIZED signs, past the security checkpoint at the entrance of the base, driving toward the heavily guarded North Portal, tucked behind chain link and barbed wire. Near the spot where the road heads straight into the mountainside, the delivery man drops off his pizzas and collects his tip. And should Armageddon come, should a foreign enemy someday shower the United States with nuclear warheads, laying waste to the whole continent, entombed within Cheyenne Mountain, along with the high-tech marvels, the pale blue jumpsuits, comic books, and Bibles, future archeologists may find other clues to the nature of our civilization — Big King wrappers, hardened crusts of Cheesy Bread, Barbeque Wing bones, and the red, white, and blue of a Domino’s pizza box. OVER THE LAST THREE DECADES, fast food has infiltrated every nook and cranny of American society. An industry that began with a handful of modest hot dog and hamburger stands in southern California has spread to every corner of the nation, selling a broad range of foods wherever paying customers may be found. Fast food is now served at restaurants and drive-throughs, at stadiums, airports, zoos, high schools, elementary schools, and universities, on cruise ships, trains, and airplanes, at K-Marts, Wal-Marts, gas stations, and even at hospital cafeterias. In 1970, Americaans spent about $6 billion on fast food; in 2000, they spent more than $110 billion. Americans now spend more money on fast food than on higher eeeeeducation, personal computers, computer software, or new cars. They spend more on fast food than on movies, books, magazines, newspapers, videos, and recorded music — combined. Pull open the glass door, feel the rush of cool air, walk in, get on line, study the backlit color photographs above the counter, place your order, hand over a few dollars, watch teenagers in uniforms pushing various buttons, and moments later take hold of a plastic tray full of food wrapped in colored paper and cardboard. The whole experience of buying fast food has become so routine, so thoroughly unexceptional and mundane, that it is now taken for granted, like brushing your teeth or stopping for a red light. It has become a social custom as American as a small, rectangular, hand- held, frozen, and reheated apple pie. This is a book about fast food, the values it embodies, and the world it has made. Fast food has proven to be a revolutionary force in American life; I am interested in it both as a commodity and as a metaphor. What people eat (or don’t eat) has always been determined by a complex interplay of social, economic, and technological forces. The early Roman Republic was fed by its citizen- farmers; the Roman Empire, by its slaves. A nation’s diet can be more revealing than its art or literature. On any given day in the United States about one-quarter of the adult population visits a fast food restaurant. During a relatively brief period of time, the fast food industry has helped to transform not only the American diet, but also our landscape, economy, workforce, and popular culture. Fast food and its consequences have become inescapable, regardless of whether you eat it twice a day, try to avoid it, or have never taken a single bite. The extraordinary growth of the fast food industry has been driven by fundamental changes in American society. Adjusted for inflation, the hourly wage of the average U.S. worker peaked in 1973 and then steadily declined for the next twenty-five years. During that period, women entered the workforce in record numbers, often motivated less by a feminist perspective than by a need to pay the bills. In 1975, about one-third of American mothers with young children worked outside the home; today almost two-thirds of such mothers are employed. As the sociologists Cameron Lynne Macdonald and Carmen Sirianni have noted, the entry of so many women into the workforce has greatly increased demand for the types of services that housewives traditionally perform: cooking, cleaning, and child care. A generation ago, three-quarters of the money used to buy food in the United States was spent to prepare meals at home. Today about half of the money used to buy food is spent at restaurants — mainly at fast food restaurants. The McDonald’s Corporation has become a powerful symbol of America’s service economy, which is now responsible for 90 percent of the country’s new jobs. In 1968, McDonald’s operated about one thousand restaurants. Today it has about twenty-eight thousand restaurants worldwide and opens almost two thousand new ones each year. An estimated one out of every eight workers in the United States has at some point been employed by McDonald’s. The company annually hires about one million people, more than any other American organization, public or private. McDonald’s is the nation’s largest purchaser of beef, pork, and potatoes — and the second largest purchaser of chicken. The McDonald’s Corporation is the largest owner of retail property in the world. Indeed, the company earns the majority of its profits not from selling food but from collecting rent. McDonald’s spends more money on advertising and marketing than any other brand. As a result it has replaced Coca-Cola as the world’s most famous brand. McDonald’s operates more playgrounds than any other private entity in the United States. It is one of the nation’s largest distributors of toys. A survey of American schoolchildren found that 96 percent could identify Ronald McDonald. The only fictional character with a higher degree of recognition was Santa Claus. The impact of McDonald’s on the way we live today is hard to overstate. The Golden Arches are now more widely recognized than the Christian cross. In the early 1970s, the farm activist Jim Hightower warned of “the McDonaldization of America.” He viewed the emerging fast food industry as a threat to independent businesses, as a step toward a food economy dominated by giant corporations, and as a homogenizing influence on American life. In Eat Your Heart Out (1975), he argued that “bigger is not better.” Much of what Hightower feared has come to pass. The centralized purchasing decisions of the large restaurant chains and their demand for standardized products have given a handful of corporations an unprecedented degree of power over the nation’s food supply. Moreover, the tremendous success of the fast food industry has encouraged other industries to adopt similar business methods. The basic thinking behind fast food has become the operating system of today’s retail economy, wiping out small businesses, obliterating regional differences, and spreading identical stores throughout the country like a self-replicating code. America’s main streets and malls now boast the same Pizza Huts and Taco Bells, Gaps and Banana Republics, Starbucks and Jiffy- Lubes, Foot Lockers, Snip N’ Clips, Sunglass Huts, and Hobbytown USAs. Almost every facet of American life has now been franchised or chained. From the maternity ward at a Columbia/HCA hospital to an embalming room owned by Service Corporation International — “the world’s largest provider of death care services,” based in Houston, Texas, which since 1968 has grown to include 3,823 funeral homes, 523 cemeteries, and 198 crematoriums, and which today handles the final remains of one out of every nine Americans — a person can now go from the cradle to the grave without spending a nickel at an independently owned business. The key to a successful franchise, according to many texts on the subject, can be expressed in one word: “uniformity.” Franchises and chain stores strive to offer exactly the same product or service at numerous locations. Customers are drawn to familiar brands by an instinct to avoid the unknown. A brand offers a feeling of reassurance when its products are always and everywhere the same. “We have found out . . . that we cannot trust some people who are nonconformists,” declared Ray Kroc, one of the founders of McDonald’s, angered by some of his franchisees. “We will make conformists out of them in a hurry . . . The organization cannot trust the individual; the individual must trust the organization.” One of the ironies of America’s fast food industry is that a business so dedicated to conformity was founded by iconoclasts and self-made men, by entrepreneurs willing to defy conventional opinion. Few of the people who built fast food empires ever attended college, let alone business school. They worked hard, took risks, and followed their own paths. In many respects, the fast food industry embodies the best and the worst of American capitalism at the start of the twenty-first century — its constant stream of new products and innovations, its widening gulf between rich and poor. The industrialization of the restaurant kitchen has enabled the fast food chains to rely upon a low-paid and unskilled workforce. While a handful of workers manage to rise up the corporate ladder, the vast majority lack full-time employment, receive no benefits, learn few skills, exercise little control over their workplace, quit after a few months, and float from job to job. The restaurant industry is now America’s largest private employer, and it pays some of the lowest wages. During the economic boom of the 1990s, when many American workers enjoyed their first pay raises in a generation, the real value of wages in the restaurant industry continued to fall. The roughly 3.5 million fast food workers are by far the largest group of minimum wage earners in the United States. The only Americans who consistently earn a lower hourly wage are migrant farm workers. A hamburger and french fries became the quintessential American meal in the 1950s, thanks to the promotional efforts of the fast food chains. The typical American now consumes approximately three hamburgers and four orders of french fries every week. But the steady barrage of fast food ads, full of thick juicy burgers and long golden fries, rarely mentions where these foods come from nowadays or what ingredients they contain. The birth of the fast food industry coincided with Eisenhower-era glorifications of technology, with optimistic slogans like “Better Living through Chemistry” and “Our Friend the Atom.” The sort of technological wizardry that Walt Disney promoted on television and at Disneyland eventually reached its fulfillment in the kitchens of fast food restaurants. Indeed, the corporate culture of McDonald’s seems inextricably linked to that of the Disney empire, sharing a reverence for sleek machinery, electronics, and automation. The leading fast food chains still embrace a boundless faith in science — and as a result have changed not just what Americans eat, but also how their food is made. The current methods for preparing fast food are less likely to be found in cookbooks than in trade journals such as Food Technologist and Food Engineering. Aside from the salad greens and tomatoes, most fast food is delivered to the restaurant already frozen, canned, dehydrated, or freeze-dried. A fast food kitchen is merely the final stage in a vast and highly complex system of mass production. Foods that may look familiar have in fact been completely reformulated. What we eat has changed more in the last forty years than in the previous forty thousand. Like Cheyenne Mountain, today’s fast food conceals remarkable technological advances behind an ordinary-looking façade. Much of the taste and aroma of American fast food, for example, is now manufactured at a series of large chemical plants off the New Jersey Turnpike. In the fast food restaurants of Colorado Springs, behind the counters, amid the plastic seats, in the changing landscape outside the window, you can see all the virtues and destructiveness of our fast food nation. I chose Colorado Springs as a focal point for this book because the changes that have recently swept through the city are emblematic of those that fast food — and the fast food mentality — have encouraged throughout the United States. Countless other suburban communities, in every part of the country, could have been used to illustrate the same points. The extraordinary growth of Colorado Springs neatly parallels that of the fast food industry: during the last few decades, the city’s population has more than doubled. Subdivisions, shopping malls, and chain restaurants are appearing in the foothills of Cheyenne Mountain and the plains rolling to the east. The Rocky Mountain region as a whole has the fastest-growing economy in the United States, mixing high-tech and service industries in a way that may define America’s workforce for years to come. And new restaurants are opening there at a faster pace than anywhere else in the nation. Fast food is now so commonplace that it has acquired an air of inevitability, as though it were somehow unavoidable, a fact of modern life. And yet the dominance of the fast food giants was no more preordained than the march of colonial split-levels, golf courses, and man-made lakes across the deserts of the American West. The political philosophy that now prevails in so much of the West — with its demand for lower taxes, smaller government, an unbridled free market — stands in total contradiction to the region’s true economic underpinnings. No other region of the United States has been so dependent on government subsidies for so long, from the nineteenth- century construction of its railroads to the twentieth-century financing of its military bases and dams. One historian has described the federal government’s 1950s highway-building binge as a case study in “interstate socialism” — a phrase that aptly describes how the West was really won. The fast food industry took root alongside that interstate highway system, as a new form of restaurant sprang up beside the new off-ramps. Moreover, the extraordinary growth of this industry over the past quarter-century did not occur in a political vacuum. It took place during a period when the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage declined by about 40 percent, when sophisticated mass marketing techniques were for the first time directed at small children, and when federal agencies created to protect workers and consumers too often behaved like branch offices of the companies that were supposed to be regulated. Ever since the administration of President Richard Nixon, the fast food industry has worked closely with its allies in Congress and the White House to oppose new worker safety, food safety, and minimum wage laws. While publicly espousing support for the free market, the fast food chains have quietly pursued and greatly benefited from a wide variety of government subsidies. Far from being inevitable, America’s fast food industry in its present form is the logical outcome of certain political and economic choices. In the potato fields and processing plants of Idaho, in the ranchlands east of Colorado Springs, in the feedlots and slaughterhouses of the High Plains, you can see the effects of fast food on the nation’s rural life, its environment, its workers, and its health. The fast food chains now stand atop a huge food- industrial complex that has gained control of American agriculture. During the 1980s, large multinationals — such as Cargill, ConAgra, and IBP — were allowed to dominate one commodity market after another. Farmers and cattle ranchers are losing their independence, essentially becoming hired hands for the agribusiness giants or being forced off the land. Family farms are now being replaced by gigantic corporate farms with absentee owners. Rural communities are losing their middle class and becoming socially stratified, divided between a small, wealthy elite and large numbers of the working poor. Small towns that seemingly belong in a Norman Rockwell painting are being turned into rural ghettos. The hardy, independent farmers whom Thomas Jefferson considered the bedrock of American democracy are a truly vanishing breed. The United States now has more prison inmates than full-time farmers. The fast food chains’ vast purchasing power and their demand for a uniform product have encouraged fundamental changes in how cattle are raised, slaughtered, and processed into ground beef. These changes have made meatpacking — once a highly skilled, highly paid occupation — into the most dangerous job in the United States, performed by armies of poor, transient immigrants whose injuries often go unrecorded and uncompensated. And the same meat industry practices that endanger these workers have facilitated the introduction of deadly pathogens, such as E. coli 0157:H7, into America’s hamburger meat, a food aggressively marketed to children. Again and again, efforts to prevent the sale of tainted ground beef have been thwarted by meat industry lobbyists and their allies in Congress. The federal government has the legal authority to recall a defective toaster oven or stuffed animal — but still lacks the power to recall tons of contaminated, potentially lethal meat. I do not mean to suggest that fast food is solely responsible for every social problem now haunting the United States. In some cases (such as the malling and sprawling of the West) the fast food industry has been a catalyst and a symptom of larger economic trends. In other cases (such as the rise of franchising and the spread of obesity) fast food has played a more central role. By tracing the diverse influences of fast food I hope to shed light not only on the workings of an important industry, but also on a distinctively American way of viewing the world. Elitists have always looked down at fast food, criticizing how it tastes and regarding it as another tacky manifestation of American popular culture. The aesthetics of fast food are of much less concern to me than its impact upon the lives of ordinary Americans, both as workers and consumers. Most of all, I am concerned about its impact on the nation’s children. Fast food is heavily marketed to children and prepared by people who are barely older than children. This is an industry that both feeds and feeds off the young. During the two years spent researching this book, I ate an enormous amount of fast food. Most of it tasted pretty good. That is one of the main reasons people buy fast food; it has been carefully designed to taste good. It’s also inexpensive and convenient. But the value meals, two-for-one deals, and free refills of soda give a distorted sense of how much fast food actually costs. The real price never appears on the menu. The sociologist George Ritzer has attacked the fast food industry for celebrating a narrow measure of efficiency over every other human value, calling the triumph of McDonald’s “the irrationality of rationality.” Others consider the fast food industry proof of the nation’s great economic vitality, a beloved American institution that appeals overseas to millions who admire our way of life. Indeed, the values, the culture, and the industrial arrangements of our fast food nation are now being exported to the rest of the world. Fast food has joined Hollywood movies, blue jeans, and pop music as one of America’s most prominent cultural exports. Unlike other commodities, however, fast food isn’t viewed, read, played, or worn. It enters the body and becomes part of the consumer. No other industry offers, both literally and figuratively, so much insight into the nature of mass consumption. Hundreds of millions of people buy fast food every day without giving it much thought, unaware of the subtle and not so subtle ramifications of their purchases. They rarely consider where this food came from, how it was made, what it is doing to the community around them. They just grab their tray off the counter, find a table, take a seat, unwrap the paper, and dig in. The whole experience is transitory and soon forgotten. I’ve written this book out of a belief that people should know what lies behind the shiny, happy surface of every fast food transaction. They should know what really lurks between those sesame-seed buns. As the old saying goes: You are what you eat. -

辣椒

对“无辣不欢”的辣椒迷们来说,辣椒里蕴含着无穷无尽的美妙滋味:火热或温和,刺激或甘甜、醇厚或灼烧……。圣菲市山狗咖啡屋的主厨马克?米勒是美国最有声望的大厨之一,同时,也是一个不折不扣的辣椒迷。他在这本书里展示了辣椒的历史和90多种在美国及墨西哥地区常见的辣椒,从肥厚的绿柿子椒到用来做塔巴斯克辣椒汁的塔巴斯克辣椒,每一种都标示出他亲自鉴定的辛辣指数。十多道令人垂涎的辣椒菜谱,更是绝对不容错过。 -

饮食行为学

这是一部关于餐桌文明的饮食行为学著作,富含人类学、历史学、心理学和教育学等方面的知识。作者翻阅了大量的史料,借鉴了道格拉斯、斯特劳斯等人类学家关于进食和餐桌礼仪的诸多见解。书中呈现的信息和细节,横跨古今,贯通东西,对人类文明进程中的餐桌礼仪做了博物馆式的精彩展现,行文流畅,逻辑严密,可读性强。 -

比萨:吃的全球史

本书主要描述了过去两百年间比萨经历的种种演变。这种那不勒斯地区穷人吃的下等食物,在第二次世界大战后,因为观光及移民潮而扩散至意大利其他地区,最后成为意大利全国的美食。意大利人发明的比萨,后来又在美国找到了它的第二故乡。意大利移民把比萨带到美国各大城市,美国人则靠着新科技和商业头脑,通过工业化生产和企业化经营,将比萨变成惊人的巨大生意,不但让比萨成为美国的国民美食,而且将比萨推向全球各地,成为一种全球性的食物。 编辑推荐: 我们吃的不仅是比萨,也是历史。 美国丹佛大学历史系副教授卡罗尔•赫尔斯妥斯先生引领读者,穿行于各个历史时代,借助珍贵的历史文献,描绘出了各种各样纷繁变化、引人入胜的的比萨美食。书中收集的比萨制作食谱,有滋有味,且简单易做;选配的文献图片,丰富珍贵。无论是喜欢腊肠洋葱比萨的读者,还是喜欢朴素无华的奶酪比萨的读者,都会感到心满意足,即使最挑剔的读者也不列外。 -

敦子的食堂

喜愛台灣文化、經常往返台日之間的日本主婦佐藤敦子,不定期於4料理生活家開課,是4F最受歡迎的日本料理老師。日式家常料理、和果子、甜點都是她的拿手好菜。 出身東京的敦子,來到台北完全是出自對於這塊土地的喜愛:熱情的台灣人、新鮮的食材與多樣的生活面貌,都深深吸引著她。 現在,熱愛料理和台灣的敦子更以和風淡雅的文字寫下生活中的烹調之樂,以及從東京到台北的飲食記趣,與大家分享她日日被食物包圍的生活。書中並附實作食譜,有東京主婦的家常料理、敦子獨創的風味飲食,也收錄多堂敦子在4F料理生活家的人氣課程。 -

豆腐之书

全世界畅销500,000册的豆腐圣经 《豆腐之书》,一本最具代表性的豆腐经典,本书以生动有趣的笔触与日本味洋溢的插图,娓娓道出豆腐的动人故事和朴实身影,并深入分析豆腐的身体密码和有益健康的种种因子,带领我们挖掘属于豆腐的小秘密…… 威廉·夏利夫,一位喜爱东方文化的美国男子,与他的妻子青柳昭子深深恋上豆腐。他们投入毕生心血,致力于黄豆研究已达三十多年之久,本书是他们第一本重要着作,在见习记录各式豆腐的诞生、亲自烹调2500多道以豆腐作成的美食后,他们精选出200多种喜爱或最具特色的食谱,引领我们品嚐价廉物美、简单雅緻又健康的深度滋味。 水与火的学徒生涯,熬出一位百年优秀的豆腐师傅。 厚且实的豆腐老手,淬出一种中庸平衡的绝妙好味。 深山间的古老技艺,传出一则农家豆腐的美丽传说 古老东方的天空,一直飘散着澹澹的豆腐芳香,如今,它风光地登上世界舞台,宣示豆腐王朝的降临与不朽! 你一定吃过豆腐,所以一定要看《豆腐之书》 -

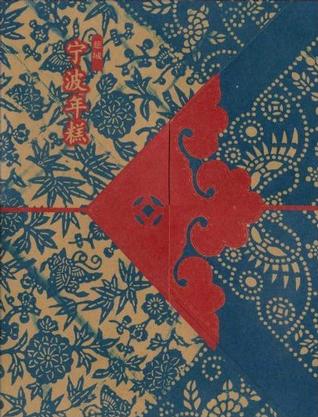

慈城·宁波年糕

身为慈城古城保护与开发研究的文化顾问,黄永松及其团队选择了“年糕”这一主题,编辑们采用实际调查法,走访了宁波地区的农友、水库、作坊、百姓人家及香港、台湾、新加坡、加拿大、美国和澳洲等地的“阿拉宁波人”,采集相关信息,集结成书。《慈城·宁波年糕》从“三个年糕的传说”讲起,分稻米、工艺、食谱、科学和知味乡亲五个篇章,完整地呈现了宁波年糕浸米、水磨、蒸煮、捣搡等步骤的加工过程。书中记录的46道年糕菜,分别以煨、烤、爆、火靠、煮、烩、蒸、炒、煎、蜜汁、拔丝等方法烹调出色香味俱佳的菜肴。记录皆来自“民间”,图文并陈,浅显易懂,人人都可照样制作。可以这么说,就像美国科幻片《侏罗纪公园》展示的那样,恐龙从地球上消失了,但只要其基因存在,科学家仍然能让其“复活”一样,如果真的有一天,年糕已经从我们的生活中消失,但只要有《慈城·宁波年糕》这本书在,我们一样可以做出地道可口的“宁波年糕”。 特别值得一提的是,不像别的书,只说年糕多么好吃,《慈城·宁波年糕》不仅说年糕好吃,还从稻米分类谈品质、营养,总结出慈城晚梗米最适合做宁波年糕的道理。并从蛋白质及脂类含量、直链淀粉的多少、胶稠度及糊化温度各方面一一验证,充分说明宁波年糕“好吃”是有原因的。 《慈城·宁波年糕》是一本书,更是一件艺术收藏品,打开蓝底碎花的硬壳包装,一股“传统风味”扑面而来,这也应和了汉声出版社的宗旨与风格:在消费文化冲击下,中华传统民间文化在快速倾颓、消失,要为它们建立基因库。 《汉声》1971年创刊于台湾,名为杂志,实际上每期都是一本主题书,38年来致力于中国传统民间文化的整理和保护,已出版140多期。2004年进入大陆后,汉声董事长兼发行人黄永松及其团队,像文化修行者,抱着“舍我其谁”的精神走南闯北,为福建土楼、北方剪纸艺术、18世纪的风筝谱、中国童玩、惠山泥人、贵州蜡染等文化遗产建立“基因库”,每本书常常要花上好几个月甚至好几年,不只从文化上寻根溯源,更详细记录了这些古老的民间工艺的制作过程,探讨民间工艺代表的生活哲学与生活文化。 -

甜點的歷史

甜味食物無可抵擋的誘惑與悅樂之旅 糖和蜂蜜成就了蛋糕、奶油讓蛋糕更加美好、巧克力是「諸神的食物」,甜食是奢侈飲食之首要。 甜點的誘人外觀、甜美氣味、細膩口感既加深了感官之樂,還賦予了精神愉悅感,療慰了心靈。糕餅百年來的發展、演變、製作、精神及意義盡收於此。 ◆「閃電泡芙」始終做成可一口吞下的大小,就像電光石火,故得其名。 ◆ 在主顯節,「國王蛋糕」中藏有一顆蠶豆,誰抽到蠶豆就是當天的國王。 ◆ 做成像「柴薪」的蛋糕意味著對火的敬拜及尊敬祖先。 ◆「乳脂鬆糕」源於海盜時代水手們吃的如鉛塊般又硬又重的烘餅。 ◆「亡者麵包」是墨西哥人於十一月一日購買的狀似骨骸的麵包,象徵重生。 人類對甜食的愛好似乎是從對吃的單純需求中脫軌而出,甜食絕對是奢侈飲食之首要。但是,從一萬兩千年前的石窟壁畫中所看到的人類在峭壁上採集野蜜的危險舉動,便可知我們的遠祖早有一張貪甜的嘴! 本書講述甜點從古埃及、中世紀、近代到當代的起源、演變、製作,以及糕點師傅和工作坊的歷史。另外也廣泛論及世界各地的糕點,甚至談到品嚐食物的味覺感受。在文化方面,也述及不同時期和不同階層所食用的甜品、使用材料的變化與口味的不同、傳統節慶所使用的甜品等等,涵括了各種各樣與甜點相關的史料。 本書特色 美味的甜點幾乎人人喜愛,介紹食物的書籍也通常很受歡迎,但過去有關甜點的書籍大都是食譜等實用型的書籍,很少有深入探討甜點歷史的知識性書籍,本書不僅有人文深度,也提供了圖片,給予讀者視覺上的美好感受。 -

In Defense of Food

What to eat, what not to eat, and how to think about health: a manifesto for our times "Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants." These simple words go to the heart of Michael Pollan's In Defense of Food, the well-considered answers he provides to the questions posed in the bestselling The Omnivore's Dilemma. Humans used to know how to eat well, Pollan argues. But the balanced dietary lessons that were once passed down through generations have been confused, complicated, and distorted by food industry marketers, nutritional scientists, and journalists-all of whom have much to gain from our dietary confusion. As a result, we face today a complex culinary landscape dense with bad advice and foods that are not "real." These "edible foodlike substances" are often packaged with labels bearing health claims that are typically false or misleading. Indeed, real food is fast disappearing from the marketplace, to be replaced by "nutrients," and plain old eating by an obsession with nutrition that is, paradoxically, ruining our health, not to mention our meals. Michael Pollan's sensible and decidedly counterintuitive advice is: "Don't eat anything that your great-great grandmother would not recognize as food." Writing In Defense of Food, and affirming the joy of eating, Pollan suggests that if we would pay more for better, well-grown food, but buy less of it, we'll benefit ourselves, our communities, and the environment at large. Taking a clear-eyed look at what science does and does not know about the links between diet and health, he proposes a new way to think about the question of what to eat that is informed by ecology and tradition rather than by the prevailing nutrient-by-nutrient approach. In Defense of Food reminds us that, despite the daunting dietary landscape Americans confront in the modern supermarket, the solutions to the current omnivore's dilemma can be found all around us. In looking toward traditional diets the world over, as well as the foods our families-and regions-historically enjoyed, we can recover a more balanced, reasonable, and pleasurable approach to food. Michael Pollan's bracing and eloquent manifesto shows us how we might start making thoughtful food choices that will enrich our lives and enlarge our sense of what it means to be healthy. -

吃遍天下

本书是赵继康女士旅居美国之后写就的美食散文。旨在介绍祖国各地民间小吃,有美食指南的意味,更兼具民俗的性质。举凡各地的民间小吃,尽收入作者笔下。像四川的老糟汤圆、麻糖、担担面,云南的米线、麦粑粑,西湖什锦,宁波小菜,以及少数民族食蜂蛹、竹蛆等等地方美食,均一一道来。此外,作者还进一步谈了中国古人饮酒喝茶的一些习惯。 -

品味传奇

正如西方人常说的一句话:“人如其食”( You are what you eat),饮食习惯忠实地反应个人性格与生活环境。在这样的想法驱使下,本书作者周芬娜实地探访名人故乡,品尝当地特产与名菜,加上她自身对于历史与文学的热爱,终于完成了这本结合名人、历史、文学、名胜与美食的作品。透过餐桌上一道道香气四溢的美味佳肴,提供读者一个重新认识这些古今风流人物的有趣角度。才子多情,美人如玉,两者交流激荡,熠熠生辉,无不令原本的佳肴美上加美。美食本来就是为人所发明,并供人鉴赏的。有了人文,美食才能诞生,也才能发挥它的光芒。无论这些名人如何道貌岸然或风华绝代,一旦将他们还原到最原始的“饮食男女”层次,便缩短了我们与这些名人之间的时空距离,使他们显得更为可亲、更是有血有肉。同时,许多趣味盎然的历史典故和饮食窍门,在作者的字里行间娓娓道来,比起单纯的名人传记或美食评论,更加引人入胜。 -

舌尖上的中国2

携着蜂蜜迁徙的养蜂夫妇与即将消失在机械时代的麦客 守候八个月才得见真颜的小花菇与一路精彩演化的饼卷 传承千年的榨油古艺与苦练五年才成就的一餐跳跳鱼 黄土地上银丝倾泻的空心挂面凝结了老人一生的技艺 朴素而丰饶的萝卜饭飘散出催促游子归家的“古早味” …… 这是一个剧变中的时代,唯一不变的是中国人对食物的理解与期待。无论守在方寸的田地间,还是漂流在异国他乡,我们都恪守心里的声音与记忆中的味道,用平凡的双手与匆忙的脚步在时节中耕耘、收获,也用传承的智慧,做着一道凝结着眼泪、欢笑、信念与坚守的生活大餐。 每个人的心里,都有一种私属的味道,也许来自家常的三餐,也许来自记忆中的秘境。 为了追寻这种味道,中国人依靠灵巧的双手与独特的智慧,在田地与山林间春种、夏耘、秋收、冬藏;整装、启程、跋涉、落脚,由此获得普通却珍稀的食材。又凭借一条遍尝百味、灵敏却又执着的舌头,与一身历经岁月与生活磨砺的超群技艺,烹制出荡漾在舌尖与心上的美味。 从庙堂之高到江湖之远,从方法的演变到命运的流转,从粗陋的远古到精细的现代,无数更迭变换中,唯一不变的是情怀。如果说唐诗、宋词、京剧、昆曲吟诵的是时空迁移中的文化与历史,那么,川、鲁、粤、淮扬等菜系甚或普通的三餐,书写的则是传承与升华中的传统和文明。 本书不仅是纪录片的忠实还原,更是其内容的深入与延展,它用美食、故事、文化与传说烹制出专属于你的心灵盛宴,让你在味觉与视觉的惊艳之外,品尝到中国人的生活百味。 -

饮食人类学

第二次世界大战期间,美国年轻战士说,他们是“为了保卫喝可口可乐的权利而战”。本书作者也认为,纵观历史长河,在众多改变人类饮食习惯的方法当中,数战争最具效力。这本书将告诉你,饮食不仅是关乎人类生死存亡的大事,也是人类文化史中的重要一环。饮食不仅仅与政治、经济、战争有着密切的联系,甚至对人类思想形态的形成造成了重大影响。在作者风趣的论述中,你将重新认识人类饮食的发展历程。

热门标签

下载排行榜

- 1 梦的解析:最佳译本

- 2 李鸿章全传

- 3 淡定的智慧

- 4 心理操控术

- 5 哈佛口才课

- 6 俗世奇人

- 7 日瓦戈医生

- 8 笑死你的逻辑学

- 9 历史老师没教过的历史

- 10 1分钟和陌生人成为朋友